Integration Testing in Python with Context Managers

UPDATE: Since this post was rather long and complex, I am currently breaking it up into several, more manageable chunks.

Summary: Complex integration tests, each involving several

simultaneously-running components, can be made simpler and faster by

judicious use of context managers and threads rather than using

subprocesses and heirarchies of unittest.TestCase objects.

I have been working on a large control and monitoring system for my clients on the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the geographic South Pole for the past few years. As the lead developer for this control system, known as IceCube Live, I am partly responsible for the overall uptime of this expensive (US$270M) detector, so reliability matters (and, if the detector goes down, I might get a phone call from Antarctica in the middle of the night…). Furthermore, with a few hundred features implemented in the code base, several developers touching the code, and constantly evolving requirements, the test coverage has to be good in order to allow changes to be made to the system with any sort of confidence. IceCube Live was developed using TDD from the beginning, and my ideas about tests have evolved as the project grew from a small prototype into a critical system for the project. I’d like to present some of these ideas here in the hope that someone else might find them useful.

Testing is most straightforward at the level of unit tests, where you can verify the behavior of individual functions and objects in relative isolation. Obviously these tests are your first line of defense, and they are usually the easiest to reason about and to write.

In larger, distributed systems, the interactions between parts can dominate the overall complexity, and integration testing is critical, particularly since subsystems that are well-tested in isolation may still not talk to each other correctly. Doing these tests right and making them run fast (important so that developers actually run them frequently) can reduce the effort and cost of maintaining the code base in the long run.

A Sample System

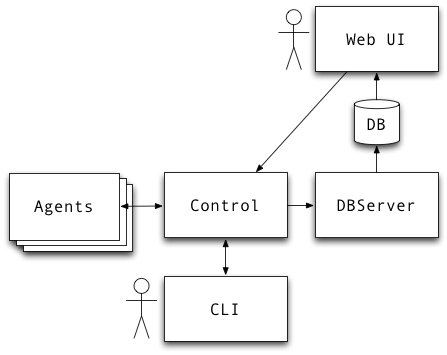

The following diagram shows a simplified system which mirrors much of the architecture of IceCube Live. The exact details of the design aren’t too important; what’s significant is that there are separate processes, possibly running on separate servers, which all interact, via RPC and/or message passing libraries.

In this case, one or more ‘agent’ programs carry out various tasks and respond to commands from Control, while also reporting to it their state and other quantities of interest. The control system has a command-line interface, but also sends all the collected information from the clients to a database server, which writes that data to a database. Finally, a Web UI accepts HTTP requests from users’ browsers, looks up recent and historical information in the database as appropriate, and returns the corresponding responses. Users of the UI can also issue commands directly to Control, via an RPC mechanism.

Though the components might run on separate machines in production, we want to run instances of each of them locally together to make sure they can talk to one another and behave correctly as they do so.

Integration Tests with ‘unittest’ and Subprocesses

A few years ago, my approach to testing features in this system would

start by using the JUnit-style unittest test library and create

subprocesses to run instances of each service. In the examples

which follow we assume a shells package which wraps the subprocess

library, providing a convenient Process wrapper to create and kill

long-running programs, and a OneOffCommand similar to Perl’s

backticks for short programs; also we have a cli command-line

program somewhere in our PATH which talks to the control program:

import unittest

import shells

class TestControl(unittest.TestCase):

def setUp(self):

self.control = shells.Process("control") # Wraps subprocess module

def tearDown(self):

self.control.kill()

def test_control_starts_ok(self):

self.assertEquals(shells.OneOffCommand("cli status"), "OK")

self.assertTrue(self.control.is_running())

# more tests...

To verify the correct connection between agents and Control, we create

the agents we need and use the ‘agents’ subcommand to our cli shell

command:

class TestAgentsWithControl(TestControl):

def setUp(self):

super(TestAgentsWithControl, self).setUp()

self.agent1 = shells.Process("agent -id 1")

self.agent2 = shells.Process("agent -id 2")

# ...

def tearDown(self):

self.agent1.kill()

self.agent2.kill()

super(TestAgentsWithControl, self).tearDown()

def test_agent_interaction(self):

self.assertEquals(shells.OneOffCommand("cli agents"), "1 2")

# ...

Now say we want to bring in the database server, to see if information from Agents is making it all the way into the database:

import MySQLdb as db

class TestDBServerWithControlAndAgents(TestAgentsWithControl):

def setUp(self):

super(TestDBServerWithControlAndAgents, self).setUp()

self.dbserver = shells.Process("dbserver")

self.db_connection = db.connect(user="milarepa", host="localhost")

# Do preparatory SQL to make sure DB is in right state, etc....

def tearDown(self):

self.db_connection.close()

self.dbserver.kill()

super(TestDBServerWithControlAndAgents, self).tearDown()

def test_data_received_in_database(self):

self.assertEquals(shells.OneOffCommand("cli start agents"), "OK")

cursor = self.db_connection.cursor()

cursor.execute("SELECT * FROM agent_updates;")

rows = cursor.fetchall()

self.assertEquals(len(rows), 2)

# ...

Finally, we want to test the views of our Web UI. These pieces should be tested on the level of individual views, but you also want to demonstrate that data is flowing through your system, end-to-end. Here we use Django’s test client to fetch URLs (Django ORM setup, etc. all omitted here):

from django.test.client import Client

class TestEndToEnd(TestDBServerWithControlAndAgents):

def setUp(self):

super(TestEndToEnd, self).setUp()

self.client = Client()

def tearDown(self):

super(TestEndToEnd, self).tearDown()

def test_agents_view_after_start(self):

self.assertEquals(shells.OneOffCommand("cli start"), "OK")

response = self.client.get("/agents")

self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 200)

# (a more correct implementation would allow for some startup time here...)

self.assertContains(response, "Agent 1: running")

self.assertContains(response, "Agent 2: running")

# ...

This strategy works, but it has a few significant drawbacks which get worse as a system grows in number of components and features:

-

Subprocesses are expensive: orders of magnitude more expensive to start compared to starting threads, for example. This becomes especially problematic as the number of tests increases, since it’s important to keep your tests running fast so that you will be encouraged to run them often;

-

The code is pretty verbose, with all the

setUps,tearDowns,super, etc. -

As your system grows in complexity, the state of the various subprocesses, database connections, etc. is spread throughout the class heirarchy, making things harder to reason about. This is largely an effect of doing setup or teardown of resources far away from where those resources are actually used. An alternative is to have separate

TestCaseswith their ownsetUpandtearDownfor every combination of resources needed, but this will lead to even more verbosity and duplication of code.

Problem 1 is addressed by running each component in its own thread rather than in a subprocess. To give you an idea of what sort of speed difference to expect:

import threading, subprocess

doproc = lambda: subprocess.Popen(["python", "-c", "'a=1'"],

stdout=subprocess.PIPE).communicate()

def dothread():

def run():

a = 1

th = threading.Thread(target=run)

th.start()

th.join()

time junk = [doproc() for _ in range(500)]

# CPU times: user 0.18 s, sys: 1.81 s, total: 1.98 s

# Wall time: 14.30 s

time junk = [dothread() for _ in range(500)]

# CPU times: user 0.09 s, sys: 0.05 s, total: 0.14 s

# Wall time: 0.16 s

That’s about a factor of a hundred in speed-up, something you will most definitely notice in your test suite.

Other advantages of threads over subprocesses in this case is that it forces you to think about thread cleanup carefully, rather than relying on the blunt, potentially messy instrument of killing processes. And it’s much easier to interrogate the state of each component when it’s running as a thread, than it is to query a subprocess (via e.g. RPC).

Problems 2 and 3 require a change of paradigms for our testing code. Enter context managers!

A brief introduction to context managers

Context managers are a way of allocating and releasing some sort of resource exactly where you need it (readers who are very familiar with context managers may want to skip this section). The simplest example is file access:

with file("/tmp/foo", "w") as foo:

print >> foo, "Hello!"

This is essentially equivalent to:

foo = file("/tmp/foo", "w")

try:

print >> foo, "Hello!"

finally:

foo.close()

Locks are another example. Given:

import threading

lock = threading.Lock()

then

with lock:

my_list.append(item)

replaces:

lock.acquire()

try:

my_list.append(item)

finally:

lock.release()

In each case a bit of boilerplate is eliminated, and the “context” of the

file or the lock is acquired, used, and released cleanly. The cool

thing about context managers, however, is that you can easily make

your own. The simplest way is with the contextlib library. Here is a

context manager which you could use to time our

threads-vs-processes testing, above:

import contextlib

import time

@contextlib.contextmanager

def time_print(task_name):

t = time.time()

try:

yield

finally:

print task_name, "took", time.time() - t, "seconds."

with time_print("processes"):

[doproc() for _ in range(500)]

# processes took 15.236166954 seconds.

with time_print("threads"):

[dothread() for _ in range(500)]

# threads took 0.11357998848 seconds.

Let’s mock up our Control object as a small object with a run function that we’ll run in a thread:

class Control(object):

def __init__(self):

self.go = False

def stop(self);

self.go = False

def run(self):

self.go = True

while self.go:

print "Control is running"

time.sleep(1)

(You could replace Control here with the real component you want to

test.)

Then we can make a control_context object which starts and stops our

Control simulator:

@contextlib.contextmanager

def control_context():

ctrl = Control()

thread = threading.Thread(target=ctrl.run)

thread.start()

try:

yield ctrl

finally:

ctrl.stop()

thread.join()

Using our context is then as simple as:

with control_context() as ctrl:

# do stuff

Context managers compose very nicely. In Python 2.7 and above, the following works:

with file("/tmp/log", "w") as log, control_context() as ctrl:

print >> log, "control state is", ctrl.state()

In Python 2.6, you can use contextlib.nested to do the same:

with contextlib.nested(file("/tmp/log", "w"),

control_context()) as (log, ctrl):

# ...

Integration Tests with Context Managers

Unlike the subclassing unittest.TestCase method, the context manager

pattern allows one to localize any needed context or state exactly

where you need it. Rather than setting up or destroying a database

connection, thread, log file or other resource “in a superclass far

far away,” you create and destroy the resources you need for only as

long as you need them. Let’s look at an example of an end-to-end test

of our toy system using context managers (and here we eschew the

unittest.TestCase boilerplate altogether, leveraging the fact that

nose will, by default, interpret any function beginning with test_

as test code to be executed):

import inspect

def cli("command"):

# ... (send an RPC message to Control) ...

def dbserver_context():

# ... analogous to control_context

def client_context(id):

# ... analogous to control_context

def wait_until(done, interval=0.01, maxtries=500):

for _ in range(maxtries):

x = done()

if x:

return x

time.sleep(interval)

raise AssertionError("The following function never returned True:\n%s"

% inspect.getsource(done))

def eq(x, y):

assert x == y, '%s %s != %s %s!' % (type(x).__name__, x,

type(y).__name__, y)

def test_agents_view_after_start():

client = Client()

def done():

response = client.get("/agents")

eq(response.status_code, 200)

return ("Agent 1: running" in response and

"Agent 2: running" in response)

with dbserver_context() as db, \

control_context() as ctrl, \

client_context(id=1) as c1, \

client_context(id=2) as c2:

eq(cli("start agents"), "OK")

wait_until(done)

The last function is more or less a complete, end-to-end integration

test for our system! I have added wait_until to poll until a

condition obtains, or raise an exception; and a simple eq to

substitute for unittest.TestCase’s assertEqual.

This is only one possible test involving components of our system. The key here is that any nested combination of setup and teardown operations is easy to obtain by composing them together as context managers. In my view this is simpler and easier to understand than by setting up heirarchies of JUnit-style test classes.

One tradeoff with this pattern is that it is can be less amenable to the “one-assert-per-test” philosophy. I claim that as the number and complexity of setup and teardown operations increases, it is less performant and more complicated to carry out the complete setup and teardown over and over again for every assert. I would rather arrange my code conceptually around the kinds of functionality being tested, wrapping related asserts in the context that they need, since I find it makes the code easier to reason about.

blog comments powered by Disqus