Communicating With Humans

“If nobody but me likes it, let it die.” – Knuth

This is the fifth post in a series about my Clojure workflow.

When you encounter a new codebase, what best allows you to quickly understand it so that you can make effective changes to it?

I switched jobs about six months ago. There was intense information transfer both while leaving my old projects behind, and while getting up to speed with new ones. I printed out a lot of code and read it front-to-back, quickly at first, and then carefully. I found this a surprisingly effective way to review and learn, compared to my usual way of navigating code on disk and in an editor solely on an as-needed basis.

If this (admittedly old-school) way of understanding a program works well, how much better might it work if there was enough prose interspersed in amongst the code to explain anything non-obvious, and if the order of the text was presented in such a way as to aid understanding?

What is the target audience of computer programs, anyways? It is clearly the machines, which have to carry out our insanely specific instructions… but, equally clearly, it is also the humans who have to read, understand, maintain, fix, and extend those programs. It astonishes me now how little attention is paid to this basic fact.

In addition to communicating, we also have to think carefully about our work. While not every programming problem is so difficult as to merit a year’s worth of contemplation, any software system of significant size requires continual care, attention, and occasional hard thinking in order to keep complexity under control. The best way I know to think clearly about a problem is to write about it – the harder the problem, the more careful and comprehensive the required writing.

Writing aids thinking, because it is slower than thought… because you can replay thoughts over and over, iterate upon and refine them. Because writing is explaining, and because explaining something is the best way I know to learn and understand it.

Literate Programming (LP) was invented by Donald Knuth in the 1980s as a way to address some of these concerns. LP has hardcore enthusiasts scattered about, but apparently not much traction in the mainstream. As I have gotten more experience working with complex codebases, and more engaged with the craft or programming, I have become increasingly interested in LP as a way to write good programs. Knuth takes it further, considering the possibility that programs are, or could be, works of literature.

Knuth’s innovation was both in realizing these possibilities and in implementing the first system for LP, called WEB. WEB takes a document containing a mix of prose and code and both typesets it in a readable (beautiful, even) form for humans, and also orders and assembles the program for a compiler to consume.

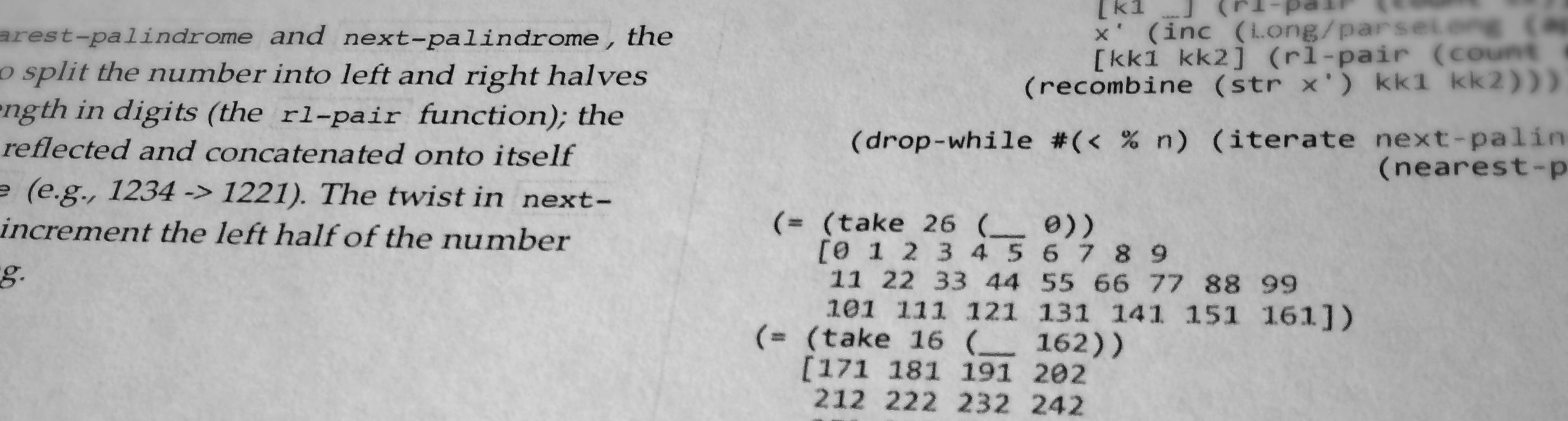

Descendents and variants of WEB can be found in use today. My favorite for Clojure is currently Marginalia, originally by Michael Fogus and currently maintained by Gary Deer.

Purists of LP will disagree that systems like Marginalia, which do not support reordering and reassembly of source code, are “true” Literate Programming tools; and, in fact, there is a caveat on the Marginalia docs to that effect… but what Marginalia provides is good enough for me:

- Placement of comments and docstrings adjacent to the code in question;

- Beautiful formatting of same;

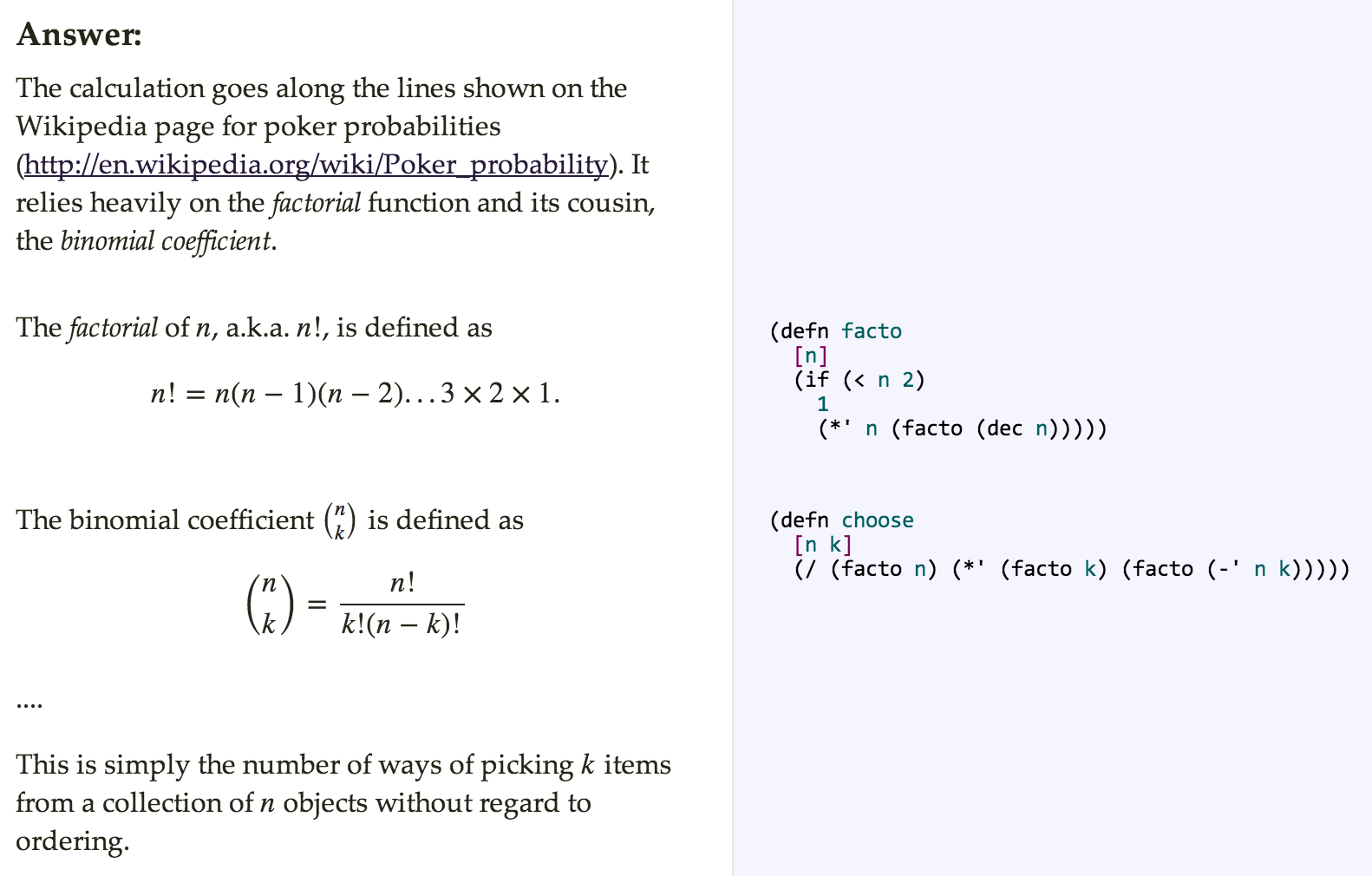

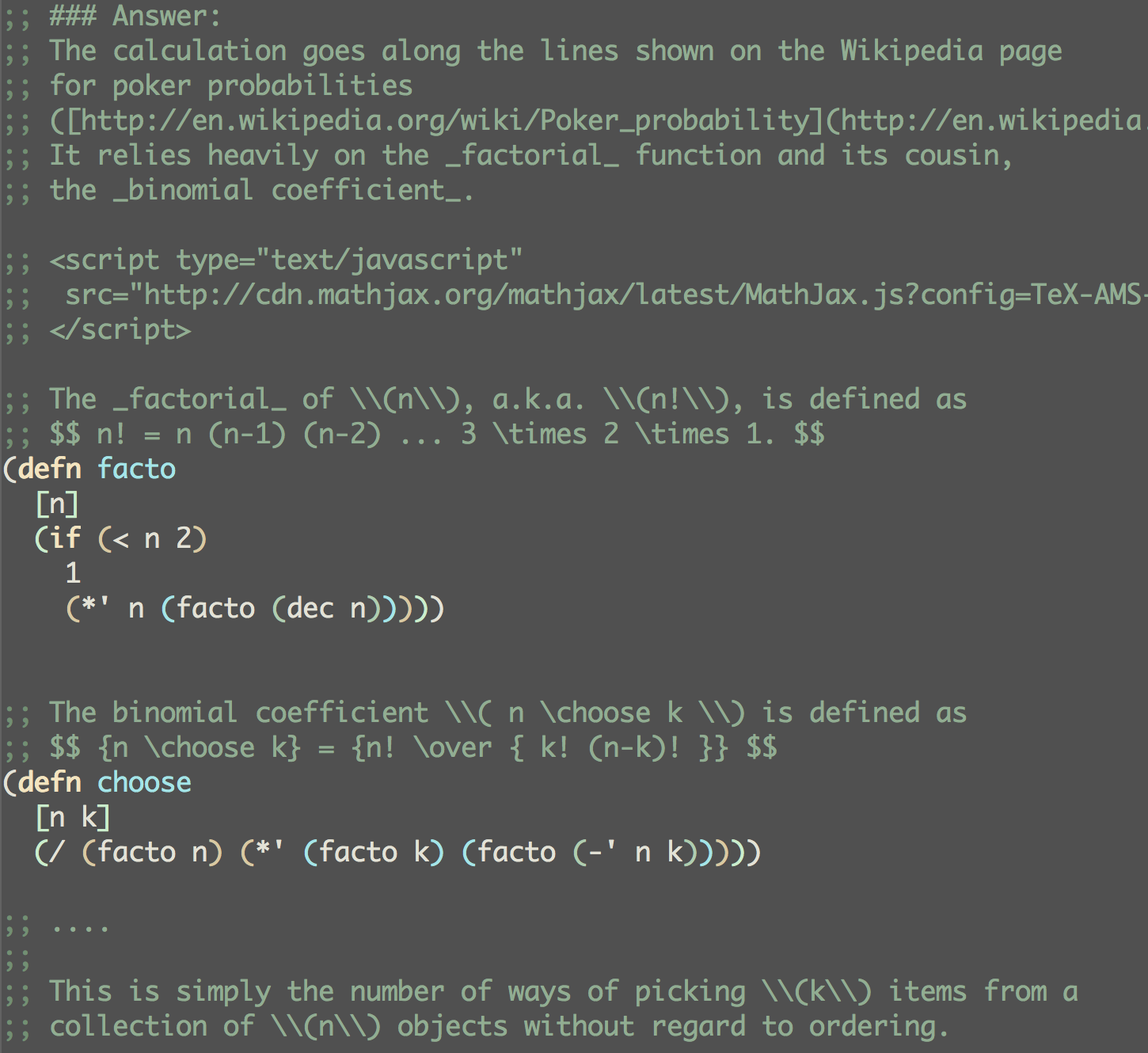

- Support for Markdown/HTML and attachment of JavaScript and/or CSS files; therefore, for images, mathematics (via MathJax) and graphing (see next blog post).

The result of these capabilities is a lightweight tool which lets me take an existing Clojure project and, with very little extra effort, generate a Web-based or printed/PDF artifact which I can sit down with, learn from, and enjoy contemplating.

The Notebook Pattern

I often start writing by making simple statements or questions:

- I want to be able to do X….

- I don’t understand Y….

- If we had feature P, then Q would be easy….

- How long would it take to compute Z?

Sentences like these are like snippets of code in the REPL: things to evaluate and experiment with. Often these statements are attached to bits of code – experimental expressions, and their evaluated results. They are the building blocks of further ideas, programs, and chains of thought. In my next post, I’ll talk about using Marginalia to make small notebooks where I collect written thoughts, code, expression, even graphs and plots while working on a problem. This workflow involves some Marginalia hacks you may not see elsewhere.

Meanwhile, here are some quotes about LP:

“Instead of writing code containing documentation, the literate programmer writes documentation containing code…. The effect of this simple shift of emphasis can be so profound as to change one’s whole approach to programming.” –Ross Williams, FunnelWeb Tutorial Manual, p.4.

“Knuth’s insight is to focus on the program as a message from its author to its readers.” –Jon Bently, “Programming Pearls,” Communications of the ACM, 1986,

“… Literate programming is certainly the most important thing that came out of the TeX project. Not only has it enabled me to write and maintain programs faster and more reliably than ever before, and been one of my greatest sources of joy since the 1980s—it has actually been indispensable at times. Some of my major programs, such as the MMIX meta-simulator, could not have been written with any other methodology that I’ve ever heard of. The complexity was simply too daunting for my limited brain to handle; without literate programming, the whole enterprise would have flopped miserably.” – Donald Knuth, interview, 2008.

blog comments powered by Disqus