This is the third post in a series about my current Clojure workflow.

Having discussed Emacs setup for Clojure, I now present a sort of idealized workflow, in which I supplement traditional TDD with literate programming and REPL experimentation.

First, some questions:

- How do you preserve the ability to make improvements without fear of breaking things?

- What process best facilitates careful thinking about design and implementation?

- How do you communicate your intentions to future maintainers (including future versions of yourself)?

- How do you experiment with potential approaches and solve low-level tactical problems as quickly as possible?

- Since “simplicity is a prerequisite for reliability” (Dijkstra), how do you arrive at simple designs and implementations?

The answer to (a) is, of course, by having good tests; and the best way I know of to maintain good tests is by writing test code along with, and slightly ahead of, the production code (test-driven development, a.k.a. TDD). However, my experience with TDD is that it doesn’t always help much with the other points on the list (though it helps a bit with (b), (c) and (e)). In particular, Rich Hickey points out that TDD is not a substitute for thinking about the problem at hand.

As an aid for thinking, I find writing to be invaluable, so a minimal sort of literate programming has become a part of my workflow, at least for hard problems.

The Workflow

Now for the workflow proper. Given the following tools:

- Emacs + Cider REPL

- Unit tests running continuously

- Marginalia running continuously, via conttest,

then my workflow, in its Platonic Form, is:

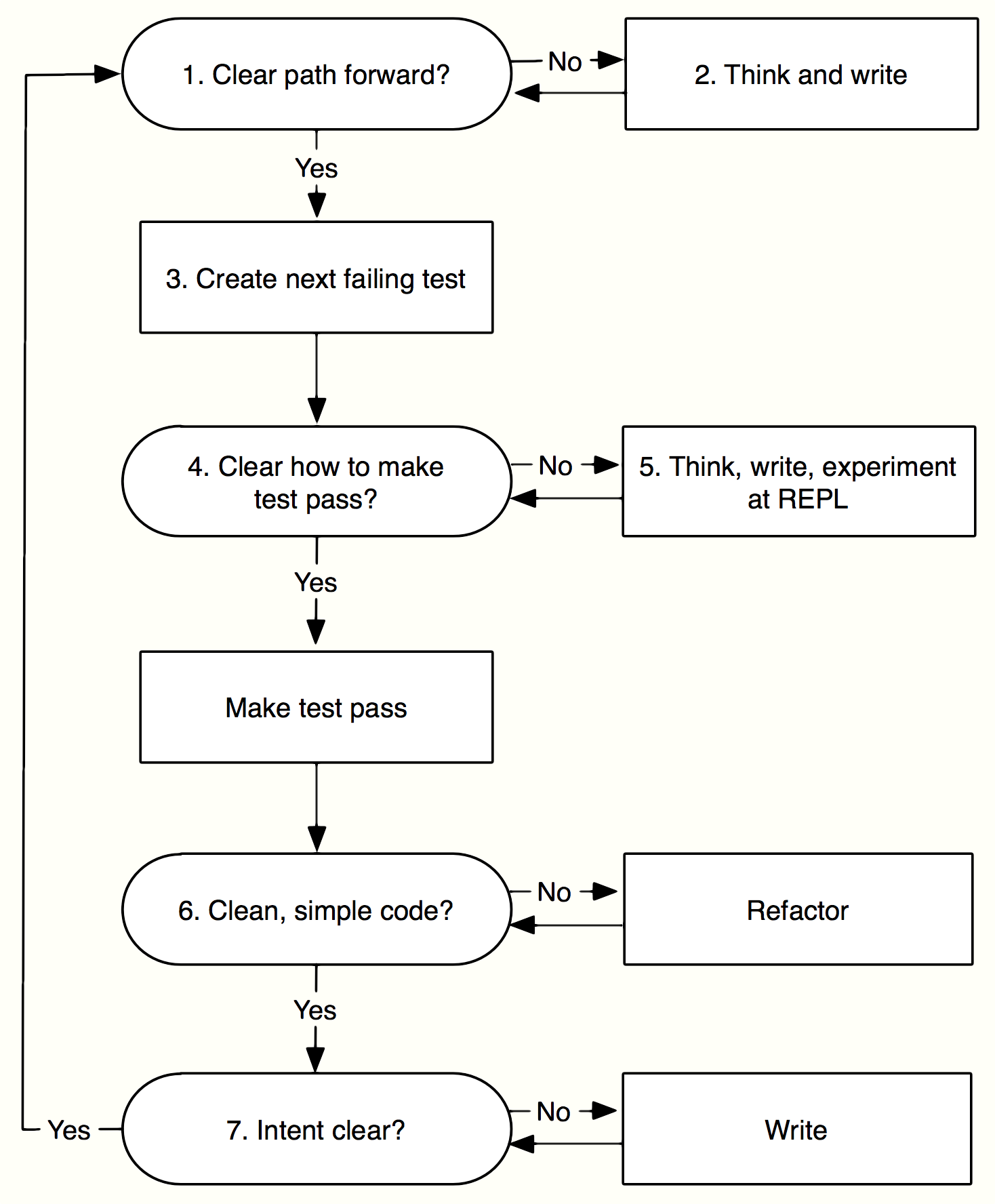

- Is the path forward clear enough to write the next failing test? If not, go to step 2. If it is, go to step 3.

- Think and write (see below) about the problem. Go to 1.

- Write the next failing test. This test, when made to pass, should represent the smallest “natural” increase of functionality.

- Is it clear how to make the test pass? If not, go to step 5. If it is, write the simplest “production” code which makes all tests pass. Go to 6.

- Think, write, and conduct REPL experiments. Go to 4.

- Is the code as clean, clear, and simple as possible? If so, go to step 7. If not, refactor, continuously making sure tests continue to pass with every change. Go to 6.

- Review the Marginalia docs. Is the intent of the code clear? If so, go to step 1. If not, write some more. Go to 7.

“Writing” in each case above refers to updating comments and docstrings, as described in a subsequent post on Literate Programming.

Here are the above steps as a flow chart:

The workflow presented above is a somewhat idealized version of what I actually manage to pull off during any given coding session. It is essentially the red-green-refactor of traditional test-driven development, with the explicit addition of REPL experimentation (“REPL-driven development,” or RDD) and continuous writing of documentation (“documentation-driven development,” or DDD) as a way of steering the effort and clarifying the approach.

The utility of the REPL needs no elaboration to Clojure enthusiasts and I won’t belabor the point here. Furthermore, a lot has been written about test-first development and its advantages or drawbacks. At the moment, the practice seems to be particularly controversial in the Rails community. I don’t want to go too deep into the pros and cons of TDD other than to say once again that the practice has saved my bacon so many times that I try to minimize the amount of code I write that doesn’t begin life as a response to a failing test.

What I want to emphasize here is how writing and the use of the REPL complement TDD. These three ingredients cover all the bases (a)-(e), above. While I’ve been combining unit tests and the REPL for some time, the emphasis on writing is new to me, and I am excited about it. Much more than coding by itself, I find that writing things down and building small narratives of code and prose together forces me to do the thinking I need in order to write the best code I can.

Always Beginning Again

While I don’t always follow each of the above steps to the letter, the harder the problem, the more closely I will tend to follow this plan, with one further modification: I am willing to wipe the slate clean and begin again if new understanding shows that the current path is unworkable, or leads to unneeded complexity.

The next few posts attack specifics about testing and writing, presenting what I personally have found most effective (so far), and elaborating on helpful aspects of each.