Updating the Genome Decoder

In our last post, we saw that so-called “N-blocks” (regions of the genome for which sequences are not available) were not getting decoded correctly by our decoder.

The solution is to look back into the so-called “file index” which specifies where the N-blocks are, and how long each block is. The modified decoder looks like this:

(defn genome-sequence

"

Read a specific sequence, or all sequences in a file concatenated

together; return it as a lazy seq.

"

([fname]

(let [sh (sequence-headers fname)]

(lazy-mapcat (partial genome-sequence fname) sh)))

([fname hdr]

(let [ofs (:dna-offset hdr)

dna-len (:dna-size hdr)

byte-len (rounding-up-divide dna-len 4)

starts-and-lengths (get-buffer-starts-and-lengths ofs 10000 byte-len)]

(->> (for [[offset length] starts-and-lengths

b (read-with-offset fname offset length)]

(byte-to-base-pairs b))

(apply concat)

(take dna-len)

(map-indexed (fn [i x] (if (is-in-an-n-block i hdr)

:N

x)))))))The primary modification is the map-indexed bit at the end, which

looks up the position of the base pair in the index using the

is-in-an-n-block function:

(defn is-in-an-n-block

([x hdr]

(let [{:keys [n-block-starts n-block-sizes]} hdr]

(is-in-an-n-block x n-block-starts n-block-sizes)))

([x n-block-starts n-block-lengths]

(let [pairs (map (fn [a b] [a (+ a b)])

n-block-starts n-block-lengths)]

(some (fn [[a b]] (< (dec a) x b)) pairs))))I tested the new decoder against FASTA files of the first two chromosomes of the human genome using the same procedure we used for yeast in my validation post. The N-blocks (and all other sequences) were decoded correctly.

The astute reader will note the use of lazy-mapcat instead of

mapcat:

(defn lazy-mapcat

"

Fully lazy version of mapcat. See:

http://clojurian.blogspot.com/2012/11/beware-of-mapcat.html

"

[f coll]

(lazy-seq

(if (not-empty coll)

(concat

(f (first coll))

(lazy-mapcat f (rest coll))))))A version of genome-sequence which used mapcat instead of

lazy-mapcat worked fine for individual chromosomes (file sections),

but consistently ran out of memory when processing whole genome files.

It took a bit of research and hair-pulling to figure out that there is

a rough edge with mapcat operating on large lazy sequences.

Lazy sequences are a strength of Clojure in general – they allow one

to process large, or even infinite, sequences of data without running

out of memory, by consuming and emitting values only as needed, rather

than all at once. Many of the core functions and macros in Clojure

operate on sequences lazily (producing lazy sequences as output),

including map, for, concat, and so on. mapcat is among these;

however, mapcat is apparently not “maximally lazy” when

concatenating other lazy seqs, causing excessive memory consumption

as explained in this blog

post.

Using that post’s fully lazy (if slightly slower) version of mapcat

fixed my memory leak as well. Though lazy seqs are awesome in many

ways, one does have to be careful of gotchas such as this one.

So, in the process of handling this relatively large dataset, we have

discovered two rough edges of Clojure, namely with mapcat and

count. We shall see if other surprises await us. Meanwhile, the

latest code is up on GitHub.

Back to Frequencies

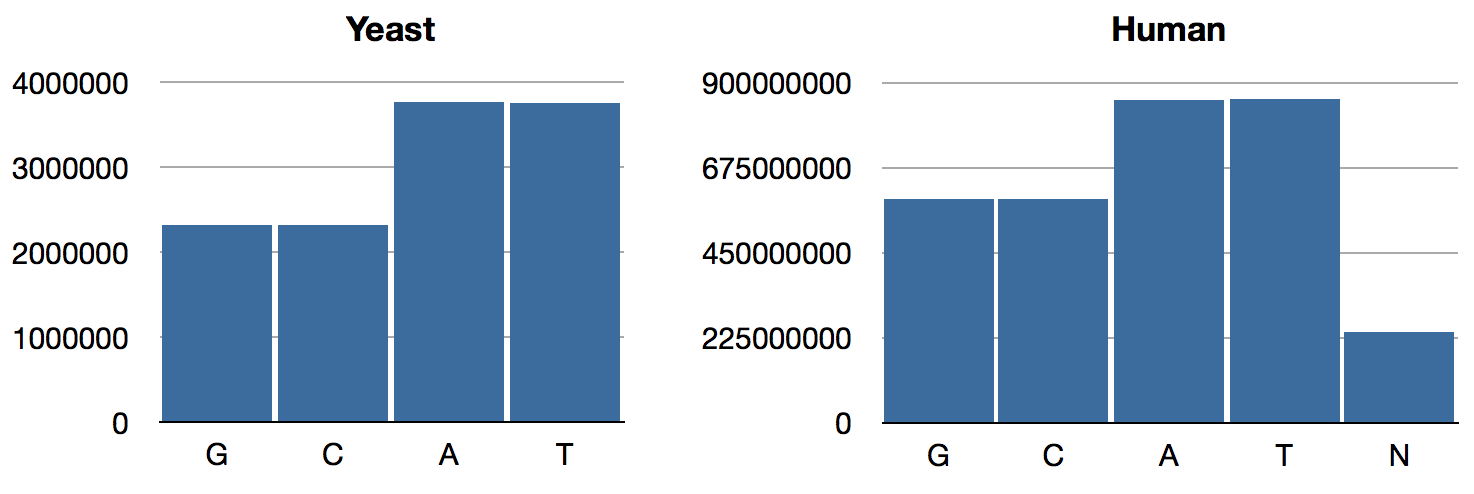

Now that we are armed with a decoder which handles N-blocks correctly, let us return to our original problem: nucleotide frequencies. For yeast, we again have:

jenome.core> (->> yeast genome-sequence frequencies)

{:C 2320576, :A 3766349, :T 3753080, :G 2317100}Same as last time. For humans,

jenome.core> (->> human genome-sequence frequencies)

{:N 239850802, :T 856055361, :A 854963149, :C 592966724, :G 593325228}As expected, the GAC numbers are the same as what we had previously; only T and N have changed. The distributions look like so:

Figure 1: Updated nucleotide frequencies

We can see that Chargaff’s Rule obtains now: A/T ratios are equal, as are G/C ratios. (BTW, this rule is intuitively obvious if you consider that in the double-helix structure, As are paired with Ts and Gs are paired with Cs.) Interestingly, the relative abundance of GC pairs in the human genome is higher than it is in yeast.

Timing and Parallelizing

Many of these “queries” on our data take a long time to run

(particularly for the human genome). So as not to tie up my REPL and

preventing me from doing other (presumably shorter) experiments, I

find it helpful to run such tasks inside a little macro (similar to

Clojure’s time) which performs the computation in a thread and, when

the task is finished, prints the time elapsed, the code that was run,

and the result:

(defmacro tib

"

tib: Time in the Background

Run body in background, printing body and showing result when it's done.

"

[expr]

`(future (let [code# '~expr

start# (. System (nanoTime))]

(println "Starting" code#)

(let [result# ~expr

end# (. System (nanoTime))

dursec# (/ (double (- end# start#)) (* 1000 1000 1000.0))]

(println (format "Code: %s\nTime: %.6f seconds\nResult: %s"

code#

dursec#

result#))

result#))))For example, our overflowing count runs as follows:

(tib (count (range (* 1000 1000 1000 3))))Starting (count (range (* 1000 1000 1000 3)))

;; ...

Code: (count (range (* 1000 1000 1000 3)))

Time: 399.204845 seconds

Result: -1294967296

Another tool which has proved useful is:

(defmacro pseq

"

Apply threading of funcs in parallel through all sequences specified

in the index of fname.

"

[fname & funcs]

`(pmap #(->> (genome-sequence ~fname %)

~@funcs)

(sequence-headers ~fname)))This threads one or more funcs through all the sequences in the file, as mapped out by

the file headers. The magic here is pmap, which is map

parallelized onto separate threads across all available cores.

pseq maxes out the CPU on my quad-core Macbook Pro and gives results

significantly faster:

Code: (->> yeast genome-sequence frequencies)

Time: 33.090855 seconds

Result: {:C 2320576, :A 3766349, :T 3753080, :G 2317100}

Code: (apply (partial merge-with +) (pseq yeast frequencies))

Time: 16.056695 seconds

Result: {:C 2320576, :A 3766349, :T 3753080, :G 2317100}

With our updated decoder and these new tools, we can continue our poking and prodding of the genome in subsequent posts.

blog comments powered by Disqus